In Bereshit 11, the Torah provides an etymology for the name of the city of בבל Bavel (Babylon in English, the capital of Babylonia). It is found at the conclusion of the famous "Tower of Babel" (Migdal Bavel) story. The people on earth all spoke the same language and began to build a city and a tower to prevent their being scattered. To prevent this scheme from succeeding, God causes them to speak different languages so they could not communicate with each other:

הָבָה נֵרְדָה וְנָבְלָה שָׁם שְׂפָתָם אֲשֶׁר לֹא יִשְׁמְעוּ אִישׁ שְׂפַת רֵעֵהוּ׃

"Let us, then, go down and confound their speech there, so that they shall not understand one another’s speech.”

וַיָּפֶץ ה' אֹתָם מִשָּׁם עַל־פְּנֵי כָל־הָאָרֶץ וַיַּחְדְּלוּ לִבְנֹת הָעִיר׃

Thus the LORD scattered them from there over the face of the whole earth; and they stopped building the city.

עַל־כֵּן

קָרָא שְׁמָהּ בָּבֶל כִּי־שָׁם בָּלַל ה' שְׂפַת כָּל־הָאָרֶץ

וּמִשָּׁם הֱפִיצָם ה' עַל־פְּנֵי כָּל־הָאָרֶץ׃

That is why it was called Babel, because there the LORD confounded the speech of the whole earth; and from there the LORD scattered them over the face of the whole earth.

(Bereshit 11:7-9, JPS translation)

It is generally accepted that this story, and particularly the etymology, is a polemic against Babylon. The Babylonians viewed their city, and their ziggurat temples (which the story of the Tower reflects) as the gateway to the gods, and that is reflected in

their etymology for their city's name. As the Online Etymology Dictionary entry for Babel

writes:

from Hebrew Babhel (Genesis xi), from Akkadian bab-ilu "Gate of God" (from bab "gate" + ilu "god"). The name is a translation of Sumerian Ka-dingir.

The Akkadian

bab is cognate with the Aramaic

bava בבא (which we discussed

here) and the Arabic

bab, both meaning gate or gateway.

However, despite the theory above that

bab-ilu is a translation from the Sumerian, others believe that this is also a folk etymology. Sarna writes in

Understanding Genesis (p. 69):

Babylon, Hebrew Babel, was pronounced Babilim by the Mesopotamians. The name is apparently non-Semitic in origin and may even be pre-Sumerian. But the Semitic inhabitants, by popular etymology, explained it as two separate Akkadian words, bab-ilim, meaning "the gate of the god." This interpretation refers to the role of the city as the great religious center. It also has mystical overtones connected with the concept of "the navel of the earth," the point at which heaven and earth meet. The Hebrew author, by his uncomplimentary word-play substituting balal for Babel has replaced the "gate of the god" by "a confusion of speech," and satirized thereby the pagan religious beliefs.

So we therefore have two folk-etymologies: one positive and one negative.

But there is one problem with the Biblical one. The root

balal בלל, as we discussed

here, means "to mix" - that is to mix different things together in one new mixture, as in the Biblical

belil בליל or the Post-Biblical

belila בלילה, meaning "mixture" or more specifically today, "batter." Yet, as Prof. Yonatan Grossman points out in his article, "

The Double Etymology of Babel in Genesis 11" this is a difficult use of

balal. After providing more examples of biblical words where

balal means mixing distinct entities, he writes:

If this is the case, it is strange to find this verb used to characterize a city in the sense of »scatter«: rather than blended or mixed, the people of the city are geographically scattered in every direction, and culturally-linguistically separated by language. Here, the verb לבלול [balal] seems to function in an antithetical sense to its usual meaning, a sense which is also antithetical to the objective of the story: at the beginning, its people were fully integrated together, but by its end, the uniform mixture has been scattered and separated.

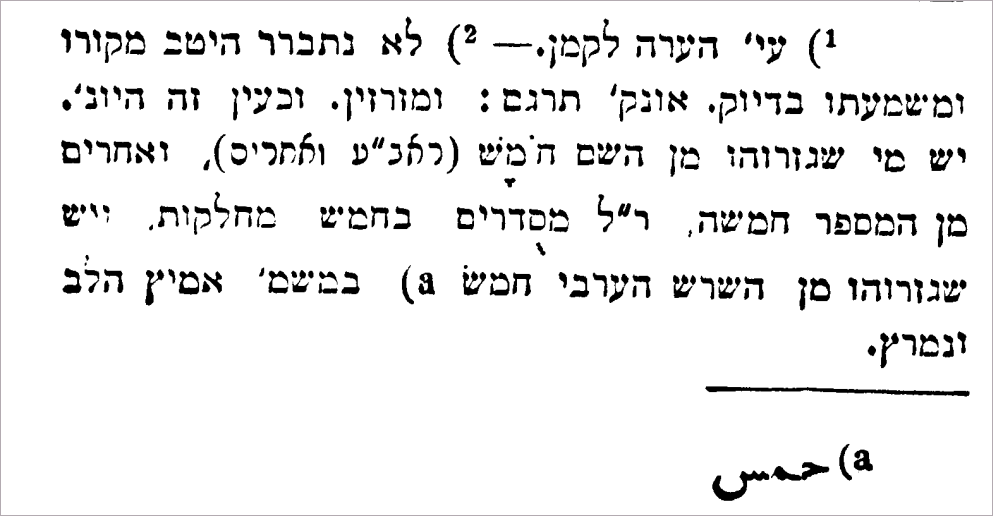

He adds that this problem is

is evident in biblical dictionaries that use two separate entries for the definition of the verb בל"ל : one referring to the sense of mixture, which appears throughout the Bible, and the second, which refers only to the Tower of Babel narrative: »there is a divine call for the mixing (›confuse‹ and ›confused‹) of the languages.

So why then does the Torah provide an etymology that doesn't seem to fit the story?

According to Grossman, this requires additional knowledge of Babylonian history. He notes that "according to

Enûma Eliš, Babylon was founded to serve as a gathering place for the gods" and that "Babylon and

Esagila are presented as the place where all the gods assemble, reside, and receive offerings." And so the root

balal serves as a second polemic:

While the Babylonians hold that their city and temple represent the place where the gods gather – where the 300 gods of the heavenly pantheon convene with the 600 gods of the underworld – the biblical narrator counters that Babylon was not a place of divine assembly but a place of human dispersion. The name is not based on a stirring motion that brings things together, but a frantic, chaotic stirring motion that drives them apart.

The essay goes into much more detail about these issues - I highly recommend reading the entire thing to fully understand the meaning behind this short but significant biblical story.

What was surprising to me was that until I read Grossman's theory, I had never heard anyone mention the problem with

balal in this context before. I assume that is because the Hebrew root בלבל

bilbel, which Klein says is related to

balal, does mean to confuse. For example, in this Mishnaic passage:

וְכִי עַמּוֹנִים וּמוֹאָבִים בִּמְקוֹמָן הֵן. כְּבָר עָלָה סַנְחֵרִיב מֶלֶךְ אַשּׁוּר וּבִלְבֵּל אֶת כָּל הָאֻמּוֹת

"And are the Ammonites or Moavites still [dwelling] in their own place? Sancheriv, king of Assyria, already arose and confused [the lineage of] all the nations." (Yadayim 4:4)

This refers to the Assyrian king,

Sancheriv, who after conquering a nation would resettle its inhabitants in other regions of his empire. And although Assyria was a Mesopotamian kingdom like Babylonia, his story is the opposite of the story of the Tower. In the Tower story, God took people speaking the same language and caused them to speak many different languages so they wouldn't be able to cooperate, Sancheriv took people of different linguistic backgrounds and mixed them together to assimilate under one unified identity.

Oh, and one last thing, since if I don't write about, I'm sure to be asked. Is there any connection between the English word "babble" and the Hebrew words that we've discussed so far?

The Online Etymology Dictionary says that

babble does not have Semitic roots:

mid-13c., babeln "to prattle,

utter words indistinctly, talk like a baby," akin to other Western

European words for stammering and prattling (Swedish babbla, Old French babillier,

etc.) attested from the same era (some of which probably were borrowed

from others), all probably ultimately imitative of baby-talk (compare

Latin babulus "babbler," Greek barbaros "non-Greek-speaking").

However, the same entry does go on to quote the OED as saying that "No direct connection with

Babel can be traced; though association with that may have affected the senses." So origin, no - but influence, possibly.